Me and History

What does the study of History mean to you?

For me, the study of History means understanding how people’s decisions and experiences have shaped them and the world we live in today.

What if anything can be gained from studying it?

Studying History, we can gain a better understanding of how the world came to be the way it is today. It helps us recognise and understand the reasons behind events, and to learn from both the successes and mistakes of the past. The only problem here is that history shows us; we don’t learn from our mistakes?

Do our backgrounds & personal perspectives affect the way we interpret history? If so, how?

Yes, they do. Our personal backgrounds, beliefs, and experiences influence what we focus on and how we interpret events. Two people can look at the same period and draw different conclusions depending on their values or cultural perspective. Imagine two photographers stood side by side focussed on the same subject? Both will have slightly different angles of view.

Do you like studying History? (be honest)

Yes.

What Is History?

History, for me is far more than a list of dates, wars, and famous people. It’s the story of humanity - of what we’ve thought, felt, and done - and the lessons we continue to learn from it. When I ask “What is history?”, I see it as both a study of evidence and a search for understanding. History is always a mix of facts and viewpoints.

Facts are fixed: they can be proven, recorded, or disproven.

But viewpoints depend on who’s telling the story and from where they speak often shaped from lived experience.

Two photographer’s viewing the same subject stood side by side will both have slightly different viewpoints.

The Origins of the Word: The term history comes from the Greek historia, meaning “inquiry” or “knowledge gained by investigation.” In Latin the word historia has the same meaning, while the Old English ‘Geschichte’ meant story or occurrences that leads to a story.

This overlap shows how storytelling and history are interwoven - both shaped by human experience, knowledge and interpretation.

Academic Perspectives:

Carl G. Gustavson saw it as “a mountain top of human knowledge” from which we can see our own generation in perspective.

This view suggests that history isn’t static - it’s a living process that helps us understand who we are and where we came from.

Alternative and Critical Views:

Henry Ford called history “bunk,” while Napoleon Bonaparte dismissed it as “a set of lies agreed upon” (quoted in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, 1955).

George Orwell warned that “the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world,” adding that this was long before the age of fake news: What he meant was, that truth itself can become flexible when people or governments - start to control information.

When enough people repeat a lie, or choose to believe a comforting version of reality, that lie begins to become fact.

Boethius, writing in the sixth century while imprisoned and awaiting execution, reflected that “The worst of times, like the best, are always passing away” (The Consolation of Philosophy). To me, this is one of the most comforting lessons history can offer. It reminds us that no moment - good or bad - is permanent. Empires rise and fall, crises come and go, and even our most painful experiences eventually become part of the past and become less painful.

History shows that both suffering and success are temporary, but the lessons they leave will last forever.

Also, let’s remember:

• The 1970s feminist movement pointed out that “History is also Her-

story too.”

• Musician Sun Ra echoed that: “History is only his story - you haven’t heard mine yet!”

Both remind us to recognise the stories that have been left out.

Why History Matters?

Dr Martin Luther King Jr. said, “We are not makers of history. We are made by history” (Strength to Love, 1963).

What I think he meant was is that none of us exist in isolation. We are all products of the times, the struggles, the values and community that came before us. History doesn’t just record events, it shapes who we become through experience. His leadership in the civil rights movement was inspired by centuries of struggle for equality, from the abolition of slavery to the peaceful resistance of Gandhi. His words remindshow me that the choices we make today are part of the story future generations will inherit. Ignoring the past will mean you are allowing its injustices to repeat themselves.

To know history is to see ourselves more clearly, not just as individuals, but as part of an on-going human journey.

Marcus Garvey wrote, “A people without the knowledge of their past, history, origin and culture is like a tree without its roots” (Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, 1923).

These words show me that history grounds us - it shapes our identity and gives us perspective.

History is a mixture of facts and viewpoints.

The first, facts, are known, documented, and quantifiable - based on research. These should not be altered, as doing so is dangerous and morally wrong.

The second, viewpoints and these depend on perspective - influenced by upbringing, experience, culture, bias, and, most importantly, what we’ve read and or learned.

Yet, as Matt Haig observed, “The main lesson of history is that humans don’t learn from

history” (How to Stop Time).

To me, history is both an investigation and inheritance - an on-going conversation between the past and the present. It shows us we must search for truth, to recognise personal bias, and to learn from what came before. Facts endure while our understanding, our viewpoints, evolve, and that I think is the true heart of history.

Britain prior to the period under study.

Britain Between the Wars and the Path to the Blitz

The Great War of 1914–1918 ended in victory, but Britain emerged weary and deeply scarred. Four years of bloodshed had drained both the economy and the spirit of its people. Millions of men returned home to a country struggling to find work for them. Prices rose sharply, wages lagged behind, and demobilisation brought unrest.

The early 1920s glittered with optimism - jazz, cinema and parties. Yet beneath the glamour lay insecurity. For most working people, post-war Britain was not a land fit for heroes but one of unemployment and discontent.

A policy of “spend and borrow” aimed to rebuild the nation through new housing and “garden cities” such as Welwyn and Letchworth. But the boom was short-lived. By the mid-1920s prosperity had faded; coal reserves were depleted, heavy industry was out-dated, and exports collapsed.

By 1932 unemployment had reached 22 percent — nearly one man in four. The General Strike of 1926 was the breaking point. When miners faced wage cuts and longer hours, other workers came out in sympathy. For nine tense days Britain stood still. Trains halted, newspapers stopped printing, and the country teetered on paralysis. When the strike collapsed, bitterness lingered. Baldwin’s Conservative government responded with the 1927 Trades Disputes Act, banning sympathy strikes and mass picketing - laws not repealed until after 1945.

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 deepened Britain’s crisis. Ramsay MacDonald, Labour’s Prime Minister, split his party to form a National Government with Conservatives and Liberals. Seen by some as betrayal, by others as duty (Morgan, 1980). Under Stanley Baldwin and later Neville Chamberlain, these governments steered Britain cautiously through austerity, a term we will become to be very familiar with.

Taxes rose from 5 to 30 percent for the middle and upper classes as the nation accepted that government must take responsibility for welfare.

Despite hardships, small reforms took a hold from mass housing and new suburban estates to the pension age being lowered to 65, education reform raising the school-leaving age to 14 and early nationalisation of coal and utilities.

These modest steps helped Britain remain stable while much of Europe turned to extremism. Yet poverty still scarred the North and South Wales, where unemployment reached 70 percent. When Jarrow’s shipyard closed, 200 men marched 300 miles to London in 1936 to demand work - the Jarrow March, a symbol of decency amid despair. Historian Andrew Marr later called the 1930s “the Devil’s Decade” (Marr, 2007, p. 143).

Across Europe, democracies fell - Spain to civil war, Italy and Germany to fascism, Russia to Stalin’s terror. Britain, though battered, remained comparatively calm - tired but wary.

Everyday life went on. Families took seaside holidays, cinemas thrived, and football crackled on the wireless. Gandhi’s visit in 1931 revealed a Britain more curious than hostile - an early glimpse of the tolerance that would later define its post-imperial identity (Brown, 2010).

Throughout the 1930s the National Governments held the political ground. They avoided the turmoil seen elsewhere but faced a grave dilemma: Germany was rearming but Britain,

still in debt from the Great War, could barely afford to match it.

Defence budgets rose gradually:

1932 – £103 million

1935 – £137 million

1938 – £400 million (= to £35 billion today) (Harrison, 1998).

Debate raged over whether to strengthen the navy, army, or air force. Ultimately, investment in the Royal Air Force prevailed - a decision that would prove critical in 1940.

The late 1930s were defined by appeasement - the belief that compromise could preserve peace. To later generations it seems naive, but at the time it reflected exhaustion and guilt. Many Britons believed the Treaty of Versailles had punished Germany too harshly (Taylor, 1961).

In 1938 Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain met Hitler in Munich and returned to cheering crowds, waving a signed paper and declaring “peace in our time.” Today; weakness by any standard.

Winston Churchill saw the danger? “An appeaser is one who feeds a crocodile… hoping it will eat him last.” (Churchill, 1948, p. 324).

Within a year, that promise was worthless. On 1 September 1939 Germany invaded Poland; two days later Britain declared war against Germany. Barely twenty-one years after the end of the Great War, Europe was once again in flames.

Chamberlain’s government stumbled after the disastrous Norwegian campaign. Facing a vote of no confidence and cries of “In the name of God, go!” he resigned. (Hansard, 1940)

Two men were contenders: Lord Halifax, who declined because he didn’t want the job anyway, and Winston Churchill, who accepted.

Taking office in May 1940, Churchill told Parliament-

“I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” (Churchill, 1940a).

Privately he admitted, “Poor people… they trust me, and I can give them nothing but disaster for quite a long time.” (Gilbert, 1991, p. 27)

Within weeks came Dunkirk - the evacuation of more than 330,000 Allied troops under fire. Churchill hailed it as “a miracle of deliverance. “We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, on the landing grounds, in the fields and in the streets, we shall never surrender.” (Churchill, 1940)

Ten days later France fell. On 17 June 1940 Hitler forced the French to sign their surrender in the same railway carriage used for Germany’s in 1918 - an act of revenge.

The Blitz and the People’s War.

With France fallen, Britain stood alone. From September 1940 to May 1941, the Blitz rained destruction on London, Hull, Coventry, and other cities.

• 43,000 civilians killed, 70,000 injured.

• 250,000 homes destroyed, 4 million damaged.

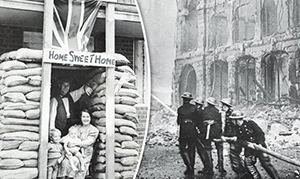

People sheltered in Underground stations, queued for rations, and carried on. Even the House of Commons and Buckingham Palace were bombed. Their resilience drew respect from the people.

One eyewitness recalled; “Everything was blown to pieces; you could see it all by the red glow reflecting from the fires that were still raging.” (Imperial War Museum Oral History, 1941)

Amidst the ruins, communities clung to courage, to hope.

Life Amidst the Blitz:

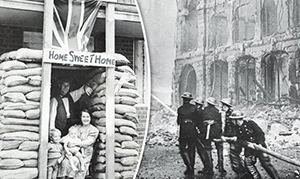

A family in a sandbagged doorway marked “Home Sweet Home.”

Children sitting among rubble.

A couple walking through the wreckage of their homes.

Up to 800,000 children were evacuated from major cities, especially London, in Operation Pied Piper. Some were gone for months, others for the duration of the war, billeted with families in Wales, Devon, and East Anglia. About 10,000 went abroad. (Green, 2006) My own mother was sent to Devon after her home in Walthamstow was bombed; her aunt was killed, and she was badly burned - not by the blast itself, but by a pan of boiling water thrown over her as the ceiling collapsed.

Rationing had been prepared from the start of the war and came fully into force in 1940. It ensured fairness but created shortages: demand far exceeded supply, and a black market soon emerged as “spivs” traded goods illicitly. (Ziegler, 2011)

The Blitz also saw a 50 percent rise in crime, particularly young offences, looting, and black-market trading. (Williams, 2012) Yet hardship drew people together more than it divided them.

The war eroded old social barriers. Families of every class sheltered side by side in Underground stations. Iron railings that once closed off London’s private squares and many properties were melted down for munitions. With rationing for all and a 50 percent top tax rate, equality was no longer just an idea - it became daily reality.

Was it truly “the People’s War”? When everyone faced the same danger, it was hard to be anything else. (Calder, 1992)

From 1942, Clement Attlee became Deputy Prime Minister, and plans began for what post-war Britain might look like. Historian Charles More notes that “Churchill did little to oppose the development of left-leaning policies for the future,” though his belief in the Empire remained strong. (More, 1985)

Commissioned in the midst of war - albeit when the tide seemed to be turning - the Beveridge Report (1942), chaired by economist William Beveridge, became an influential document shaping the reforms that followed.

Its two main aims were clear:

The creation of a welfare state, ensuring social security “from the cradle to the grave” (Beveridge, 1942).

The eradication of mass unemployment through to planned reconstruction and government responsibility for jobs and welfare.

The report also identified the five “Giant Evils” holding society back, Want, Ignorance, Squalor, Idleness, and Disease.

The aim was simple: to look after British people - literally from the cradle to the grave.

And by far the most famous and transformative result was the National Health Service Act (1946), inaugurated in 1948 - the birth of the NHS. It became the crown jewel of post-war Britain: free healthcare for all, funded by the state, and a lasting legacy of the unity and sacrifice forged in war (Le Grand, 2019).

The creation of the National Health Service was both a revolution and a revelation. It began modestly, with a patchwork of voluntary hospitals and municipal infirmaries brought together under one national system. The first NHS hospital, Park Hospital in Manchester - now Trafford General - opened its doors on 5 July 1948 (NHS England, 2023). For the first time, treatment was free at the point of need, regardless of class, income, or background. Doctors and nurses who had once worked for private charities or local councils now served a national cause. It was a profound statement of collective care - the embodiment of Beveridge’s vision that no citizen should be left behind.

From those beginnings, the NHS grew into a model admired around the world. Its principles of universal access, publicly funded care, and compassion in practice inspired similar systems from Scandinavia to New Zealand. In seventy-five years it has faced relentless pressure - from pandemics to politics - yet it remains Britain’s greatest civic achievement.

Today, despite its struggles, the NHS stands as a reminder of what emerged from the hardships of war, a belief that a fair society must care for its people, not just as a charity case, but as a shared right.

Conclusion:

From the ruins of 1918 to the defiance of 1940, Britain endured depression, war, and social change. Out of hardship came unity. The inter-war reforms - in housing, welfare, and education - laid the groundwork for a new social contract.

When Churchill offered only “blood, toil, tears, and sweat,” he spoke to a people already worn down by two decades of struggle. Their endurance in the Blitz, their humour in adversity, and their faith in fairness became the foundation of victory - and of a fairer Britain to come.

Post-War Britain: The Spirit of ’45

Although Britain had just emerged victorious from the Second World War under Winston Churchill’s leadership, the 1945 General Election produced a stunning result: Labour won a majority of 146 seats while Churchill’s Conservatives were defeated. On the surface, this seemed inexplicable given Churchill’s personal popularity of around 78% (Addison, 1994).

After the war came a strong desire for a “people’s peace.” Many Britons hoped the shared sacrifices of wartime would lead to a fairer post-war society. Churchill, though admired, carried a warmonger attitude and this isn’t what the people wanted, this no longer suited the public mood. What the country wanted now was stability, housing, work, and a government that would look after ordinary people. Labour captured that feeling, offering something new for peacetime while the Conservatives looked rooted in the past (Pelling 1984).

Many expected Churchill to “walk it,” but voters wanted change after years of war.

Labour promised a “people’s peace” – rebuilding, welfare, and fairness – rather than a return to old politics. Churchill was seen as the right man for war, but not for peace. The result reflected hope for a better, more equal Britain (Morgan, 1987).

The Labour Party emerged from the election with growing political power. Working people and the trade unions in the early twentieth century gained strength. The Unions’ purpose was to represent workers’ interests and to promote greater social and economic equality (Thorpe, 2015).

Clause IV of the Labour Party constitution, first drafted in 1918, famously declared the aim of securing “the common ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange” (Labour Party, 1918). This phrase demonstrated Labour’s long-term vision of a fairer society, where wealth and opportunity were shared more evenly.

Then came the Beveridge Report commissioned in the midst of war, albeit when it was felt that the tide was perhaps on the turn in the war, chaired by economist William Beveridge, became an influential document in the post-war reforms that followed and in the creation of a new Welfare State (Beveridge, 1942).

The report identified five “giant evils”: Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor, and Idleness.

Beveridge’s proposed solution was a ‘cradle to the grave’ system of social insurance, ensuring that no citizen would fall through the cracks in times of need. This was to become known as National Insurance (NI contributions). This was a system that was means paid, the richer paid more while the poor paid less.

It became a wartime bestseller with a staggering 600,000 copies sold, showing how deeply the British public embraced the vision of a fairer, more secure post-war society (Hennessy, 1992).

As Labour Party leader, the creation of the Welfare State, in particular the NHS, was Clement Attlee’s crowning glory, albeit that it was Nye Bevan’s “baby” (Bevan, 1952).

Labour’s 1945–1951 government introduced sweeping reforms based on Beveridge’s ideas. In six short years, they passed 347 Acts of Parliament, transforming Britain into a welfare democracy (Morgan, 1984).

Key legislation included:

Family Allowances Act (1945) – payments to families for each child.

National Insurance Act (1946) – established sickness, unemployment, and old-age benefits.

National Assistance Act (1948) – support for those not covered by National Insurance.

Town and Country Planning Act (1946) – reshaped cities and required planning permission for new development.

New Towns Act (1951) – built new towns to house hundreds of thousands of people (Addison, 1994).

These measures collectively built the foundations of modern Britain.

Bevan’s Vision for a Healthier Nation led to the NHS which was implemented by Aneurin (Nye) Bevan on 5th July 1948 (Harris, 1997).

Sheer determination meant that the bulk of the work was achieved in six hectic months.

Bevan, who had grown up in poverty in the Welsh coalfields, had long believed that “there must be a better way of organising things” (Bevan, 1952).

Park Hospital in Manchester was to become the first NHS hospital. For the first time, hospitals, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, opticians and dentists were brought together under one umbrella organisation to provide services free at the point of delivery.

The NHS was the most ambitious and expensive reform ever conceived. Doctors and other highly paid medical staff resisted nationalisation, fearing loss of independence (Webster, 2002).

In fact, Conservative MPs voted against a free for all NHS 22 times, including at its final reading - something that contradicts later claims that the Conservatives were responsible for its creation (The Independent, 2017).

Nevertheless, Bevan persisted. The central principle was simple yet revolutionary:

Healthcare available to all, financed entirely by taxation, according to means and free at the point of need (Timmins, 1995).

Indeed, from that first hospital opening, within hours the phones were overrun from calls as small surgeries and community hospitals clamoured to get on board.

In the immediate post-war years, austerity became synonymous with Stafford Cripps, Labour’s Chancellor from 1947 (Zweiniger-Bargielowska, 2000). The people were to face this term again in more recent years.

Britain’s economy was fragile, exports had collapsed, and rationing, astonishingly, was often stricter than during wartime.

Cripps’ policies aimed to restore balance through rationing, wage freezes, and import cuts.

Even bread was rationed for the first time between 1946–48, largely because Britain was feeding occupied Germany (Hennessy, 1992).

Rationing slowly eased from 1948, but key items like tea, butter, and meat remained rationed until 1954 - the longest of any country.

These sacrifices tested the public’s patience. The war was over, yet people still queued for basics, while taxes remained high and wages remained low and controlled.

By 1949, the economy had begun to recover, though devaluation of the pound increased import prices. Despite economic constraints, Labour pressed ahead with social progress.

In 1949, Lewis Silkin, Minister of Town and Country Planning, introduced the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Bill, calling it “a people’s charter” (Silkin, 1949).

It created National Parks, nature reserves, long-distance footpaths, and legal access rights to the countryside. Silkin declared: “This is not just a bill. It is a people’s charter - for the open air, for hikers and ramblers, for everyone who loves to get out into the countryside and enjoy it.”

The Attlee government had remade Britain - from health and housing to education, planning, and welfare - in just six transformative years (Addison, 1994).

Was this a period of national unity?

Amongst the people perhaps. Returning soldiers felt they had earned a new life for themselves and their families; this was the reward they felt they had earned for their sacrifices. With this was the din of cries of “never again” (Harris, 1997).

Among the ruling elite, less so. The Conservatives broadly accepted some nationalisation and full employment, but they fiercely opposed the scale and cost of Labour’s welfare plans, particularly the NHS (Morgan, 1987).

Historians remain divided; Calder and Pelling argued that the war made little real difference, and that such reforms would have come anyway (Calder, 1969; Pelling, 1984). However, Addison and Marwick disagreed, insisting that the wartime experience reshaped public expectation (Addison, 1994; Marwick, 1970).

Having fought for their country, Britons demanded reward - for themselves and their children.

The war, they said, made reform inevitable because it unified the population and proved that collective action could work (Harris, 1997).

Despite internal strain and constant financial pressure, Attlee believed Labour’s 1945 win guaranteed “a good ten years” in power (Attlee, 1954).

At the 1950 party conference, the tone was triumphant: “Poverty has been abolished, hunger is now unknown, the sick are tended, the old folk are taken care of, and our children are growing up in a land of plenty” (Labour Party, 1950). A moving declaration, though perhaps a little premature.

The 1950 election was a narrow victory, but with a majority of just five. In 1951, Labour actually won more votes than the Conservatives, yet fewer seats, and they therefore lost power (Pelling 1984).

This was a shocking turnaround for both the people and the Conservatives.

Attlee, who had so often snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, could not do so this time.

The electorate didn’t buy Labour’s warnings about Churchill’s return - the slogan “Whose finger is on the trigger?” failed to resonate (Morgan, 1987).

And so, at age 77, Churchill returned to Downing Street, with Anthony Eden handling most of the day-to-day running of the country (Hennessy, 1992).

By the early 1950s, Britain’s wartime unity had given way to exhaustion. The optimism of 1945 was fading fast (Addison, 1994).

The people were tired of rationing, tired of housing shortages, tired of strict control and tired of austerity, which had become synonymous with Labour itself.

It was a complete turnaround in mood which was deeply ironic, given the idealism that had swept them to power six years earlier.

As well as the electorate being tired of post-war hardship, the Labour Party itself was divided; a split that would persist for years. Internal disagreements over economic control, foreign policy, and defence spending weakened their unity just as the Conservatives were recovering strength and improving their electability (Morgan, 1987).

More than anything, the enormous £6 billion spent on rearmament left Britain in a fragile financial position. The nation had grown uneasy with what many called the “economic rollercoaster” of Labour’s stewardship (Hennessy, 1992).

Perhaps this was their ultimate problem: they did too much, too soon, and were punished for their ambition.

History has been kinder than the electorate of 1951. With hindsight, many now regard Attlee’s government as the most transformative administration in British history; architects of the NHS, the welfare state, and post-war reconstruction (Addison, 1994; Morgan, 1987). Their achievements reshaped Britain’s moral landscape and set a precedent for compassion in governance.

The Conservatives pledged to end Labour’s austerity by cutting defence spending and managing the economy more tightly. Yet despite Labour’s monumental achievements, Attlee’s hoped-for ten years in power never came to pass (Hennessy, 1992).

Labour was again consigned to the political dustbin, where it remained for almost 13 years of Conservative rule; 13 years which Labour would later brand “the thirteen wasted years” (Morgan, 1987).

Ironically, those years continued under the very framework Attlee had built; a welfare state, an NHS, and a new social contract that no government could easily undo.

Consumerism & Consensus (The 50’s and 60’s) 1

Summary

The 1950s and 1960s in Britain were marked by optimism, stability, and significant social change. After the upheaval of the Second World War, the country entered an era of political consensus and economic growth. Living standards rose, unemployment remained low, and the welfare state established by Attlee’s post-war government became an accepted part of national life. The Conservatives, beginning with Churchill and culminating in Macmillan’s leadership, largely maintained Labour’s reforms while overseeing a period of affluence often described as “the never had it so good” years. Rising wages, consumer goods, and the spread of television and popular culture created a more confident, modern society. Yet beneath this prosperity were concerns about Britain’s declining industrial competitiveness and its uncertain world role following the loss of empire. Harold Wilson’s arrival in the mid-1960s signalled a new emphasis on modernisation and technological progress, as the country sought to redefine itself amid shifting global and domestic realities.

Consumerism:

Consumerism became the defining social trend of post-war Britain. Rising wages, full employment, and easier credit gave people unprecedented spending power. Families invested in household appliances such as washing machines, televisions, and refrigerators, which transformed domestic life and reduced drudgery. Ownership of cars and the growth of leisure industries-from holidays to home entertainment-symbolised freedom and prosperity. Advertising and mass media fuelled desires for new products, linking consumption with identity and happiness. By the mid-1960s, spending on non-essential goods had surpassed essentials, marking Britain’s transformation into a consumer society that celebrated material comfort and personal choice as indicators of success.

Consensus:

The post-war consensus defined British politics from the late 1940s to the mid-1960s. Both Labour and Conservative governments accepted the principles of the mixed economy, full employment, and the welfare state. This shared outlook-sometimes termed “Butskellism” (combining the names of Conservative Chancellor R.A. Butler and Labour's Hugh Gaitskell. It characterized a centrist approach that accepted a mixed economy, a strong welfare state, and the use of Keynesian policies (Keynesian policies are government measures that manage aggregate demand to stabilise the economy. In recessions, governments boost spending, cut taxes, or lower interest rates to stimulate demand and jobs. During inflation, they do the opposite-raising taxes or reducing spending to slow the economy to ensure full employment and a degree of social collaboration) - meant there were few ideological divides over core economic and social policies. The NHS, public housing, and education reforms enjoyed bipartisan support, while moderate trade union relations sustained industrial peace. Political stability fostered social cohesion and rising prosperity, though critics later argued that consensus bred complacency and masked deeper economic weaknesses. Nonetheless, it provided the framework for Britain’s reconstruction and relative harmony during these decades.

Conflict & Change (The 50’s and 60’s) 2

The 1950s and 1960s marked one of the most transformative periods in modern British history, decades in which the established social ladder, moral certainties, and cultural identities were challenged and redefined. The post war “consensus” that had characterised Britain politically and economically began to fracture under the pressure of rapid social, cultural, and ideological change (Clarke, 1996). From the Lady Chatterley’s Lover obscenity trial to the Profumo Affair, Britain’s sense of morality was publicly debated and often ridiculed. These incidents symbolised a growing appetite for openness and honesty about class, sex, and authority, issues that would come to define the 1960s (Donnelly, 2005).

The rise of youth culture was perhaps the most visible expression of this new mood. The so-called “youthquake” of the 1950s and early 1960s brought with it the Teddy Boys, Mods and rockers and later, the Hippies, groups who redefined identity, fashion, and belonging (Osgerby, 2005). The influence of American rock and roll transformed British music, while bands such as The Beatles, The Who, and The Rolling Stones came to symbolise rebellion and modernism while in parallel, cinema and literature reflected this shift, capturing both the optimism and disillusionment of a changing nation through social realism and satire (Booker, 1970).

Political and legislative reform deepened this sense of transformation. Landmark acts such as the Abortion Act (1967), the Sexual Offences Act (1967), and the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act (1965) marked a decisive move toward a more liberal and permissive society (Hall, 2005). Yet the same period also exposed the limits of progress. For many, the “Swinging Sixties” were confined to a privileged few in London, while traditional values and inequalities persisted across much of Britain (Sandbrook, 2006). Figures such as Mary Whitehouse embodied this backlash, accusing modern Britain of moral decline.

Historians remain divided on how far-reaching this change truly was. Sandbrook (2006) describes it as a “veneer of modernity”, a surface level transformation affecting mainly the middle classes, whereas Marwick (2011) views it as a genuine social revolution that altered relationships between generations, genders, and social classes. Whether viewed as revolution or illusion, the period undeniably redefined Britain’s identity. The old world of respect and conformity gave way, however imperfectly, to a society more questioning, expressive, and self-aware.

Change:

The theme of change in the 1950s and 1960s centres on a gradual but unmistakable transformation of British society. The nation moved from post war austerity to a new culture of consumerism, freedom, and youth expression (Marwick, 2003). Legislative changes such as the Abortion Act and Sexual Offences Act reflected a profound liberalisation of law and morality, while developments in fashion, film, and music mirrored a growing appetite for experimentation and individualism (Hall, 2005). The emergence of youth cultures, from the Mods through to the Hippies, represented a generational shift towards self-expression and rejection of authority (Osgerby, 2005).

This period also saw the expansion of higher education, particularly following the Robbins Report, which democratised access to universities and symbolised a belief in social progress (Morgan, 2001). Yet, change was uneven: while women gained greater control over their lives, genuine equality remained elusive (Sandbrook, 2006). While London “swung”, much of Britain did not. The 1960s therefore stand as both a decade of unprecedented transformation and a reminder that progress often brings new contradictions and inequalities.

Conflict:

Conflict lay at the heart of Britain’s transformation during the 1950s and 1960s. Beneath the optimism and creativity of the era ran deep divisions over class, gender, race, and morality (Clarke, 1996). The Chatterley Trial and the Profumo Affair exposed tensions between an emerging liberal culture and a conservative establishment desperate to maintain control (Donnelly, 2005). Generational conflict intensified as youth cultures challenged traditional respectability through fashion, music, and defiance, vividly embodied in the clashes between Mods and Rockers (Osgerby, 2005).

Social reform provoked fierce moral opposition, typified by Mary Whitehouse and her campaign against “permissiveness” (Hall, 2005). Racial tensions also surfaced, as immigration and Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech revealed a society struggling to redefine itself in a post imperial world (Fry, 2004). Even within culture, conflict persisted, between commercialism and authenticity, between liberation and exploitation, between those who felt empowered and those who felt alienated. These tensions underpin the debate between Sandbrook and Marwick: whether the sixties were a genuine revolution or simply a struggle between competing visions of what Britain should become (Sandbrook, 2006; Marwick, 2011).

Stanley Cohen’s ‘Folk Devils and Moral Panics’ (1972) examines how British society in the 1960s responded to the conflicts between two youth subcultures, the Mods and the Rockers, and how these reactions reveal the dynamics of social control. The Mods, known for their scooters, sharp suits, and love of soul music, and the Rockers, associated with motorbikes, leather jackets, and rock and roll, clashed in seaside towns such as Southend, Clacton, Margate, and Brighton. Although these confrontations were often small and contained, the media sensationalised them, portraying the events as large-scale riots and the youths as symbols of moral decline.

Cohen argued that this media-driven exaggeration created a “moral panic”, a collective overreaction in which the Mods and Rockers became “folk devils”, scapegoats blamed for wider social anxieties about changing values, class tensions, and youth rebellion. Newspapers, politicians, and police reinforced each other’s alarm, leading to stricter policing and harsher punishments that far exceeded the scale of the actual disturbances.

The concept of moral panic, which first developed in this study, shows how societies construct and amplify deviance. Rather than focusing on the young people’s behaviour itself, Cohen highlighted how institutions define what counts as a threat and use it to reassert moral boundaries. His analysis remains influential because it explains how fear and exaggeration can turn minor acts of deviance into national crises, reflecting not the actions of a few youths but the insecurities of an entire culture confronting social change.

Britain and the Wider World (1945 – 1969)

Despite victory in two world wars, Britain emerged from 1945 profoundly changed. The country that had once ruled over vast territories across every continent, “the empire on which the sun never sets”, was now weary, indebted, and facing a world transformed. Though still in possession of a large empire, Britain’s global dominance was ebbing away. Over the next two decades a steady domino effect of decolonisation would bring the imperial era, which had shaped British identity for centuries, to an end.

It was in this context that Adolf Hitler’s bitter wartime prophecy appeared, in part, to come true. Nearing the end of the war, he declared: “Whatever the outcome of this war, the British Empire is at an end. It has been mortally wounded” (The Testament of Adolf Hitler, 1961, p. 34). His gloating remark that the British people would “die of hunger and tuberculosis on their cursed island” was filled with spite, but it carried a chilling recognition that the empire’s power could not survive a second global conflict.

In one sense, history vindicated him. The war left Britain victorious but economically crippled. Wartime debts, especially to the United States, were overwhelming, and the cost of maintaining empire alongside ambitious new welfare commitments at home proved impossible. Within two decades, India, Pakistan, and most of Africa had achieved independence, and Britain’s status as a global power was fundamentally diminished. Yet Hitler’s ultimate prediction was wrong: Britain did not wither. Instead, it adapted, reshaping itself as a modern nation bound more by cooperation than conquest.

A New Reality: Great Nation or Great Power?

Wartime hero Winston Churchill recognised early that the future of Europe lay in unity, not empire. In his 1946 Zurich speech, he called for a “United States of Europe” where nations could “dwell in peace, in safety, and in freedom” (Churchill, 1946). Yet tellingly, he did not include Britain within that union. Churchill saw Britain as standing apart, culturally tied to the United States and historically bound to the Commonwealth.

This sense of exceptionalism captured the new dilemma: Britain still saw itself as global in spirit, but the means to sustain that vision were slipping away.

Britain’s post-war leaders, Attlee, Churchill, Eden, Macmillan, and Wilson, wrestled with this identity crisis. They were united in their desire to preserve international stature, yet divided over how. Churchill and Eden clung to the grandeur of empire and the illusion of independent power; Attlee and Macmillan accepted that survival meant partnership, through the Commonwealth, NATO, and alignment with the U.S.

Scientific adviser Henry Tizard defined the moment with a blunt warning: “We are a great nation, but if we continue to behave like a great power, we shall soon cease to be a great nation” (Tizard, c.1949). His words reflected the new reality: Britain’s strength now lay not in empire but in recovery, rebuilding its economy, investing in science and welfare, and adapting to a world where prestige was earned through stability rather than domination.

Yet accepting decline was emotionally and politically painful. A people who had endured hardship to “win the war” struggled to grasp that their victory had changed little in material terms. The balance of power had shifted across the Atlantic, and Britain was learning, sometimes reluctantly, that diplomacy, not domination, would define its future.

Economic Burdens and American Dependence

Economically, Britain’s position after 1945 could be summed up in one word: debt. Economist John Maynard Keynes, advising Attlee’s Labour government, warned that Britain’s global role had become “a burden which there is no reasonable expectation of our being able to carry” (Keynes, 1945). The country’s war debts equalled nearly three times its national income, and while its cities and industries were rebuilding, its empire still demanded troops, garrisons, and administrators.

At home, the new Labour government embarked on the bold social reforms promised during wartime, the founding of the National Health Service, the expansion of social security, and major public housing programmes. These measures transformed British life but deepened the financial strain. At the same time, Britain maintained costly forces across its remaining colonies and in newly occupied Germany, while also funding its role in Korea and the early Cold War.

Britain’s wartime survival had depended heavily on U.S. support. The Lend-Lease programme had provided weapons, fuel, and food throughout the conflict, but when it ended abruptly in 1945, Britain was left exposed. Attlee’s government secured new American and Canadian loans totalling billions, but these came with strings attached: the U.S. demanded trade liberalisation and a continuing military presence on British soil.

The subsequent Marshall Plan (1948) provided further relief, around $2.7 billion in American aid, more than any other European country received. But, as historian Corelli Barnett later observed, Britain used much of this aid to prop up existing industries rather than modernising. The money eased austerity but did little to rebuild competitiveness (Barnett, 1986). The result was an illusion of recovery masking deep dependency.

Thus was born the so-called “special relationship.” It bound Britain and the U.S. together through shared language, culture, and ideology, but beneath the rhetoric lay economic necessity. Britain had traded its financial independence for post-war survival.

Testing Power: Korea and Suez:

Britain’s new limits were soon tested. When North Korea invaded the South in 1950, Attlee’s government joined the U.S.-led United Nations coalition. Officially, the Korean War represented a defence of democracy; unofficially, it was an attempt to show that Britain still counted. Troops fought bravely alongside Commonwealth allies, yet the war’s strategic and financial cost outweighed any prestige gained. The conflict reinforced Britain’s dependence on American leadership, its place in the world increasingly that of a loyal ally rather than an independent power.

The Suez Crisis of 1956 finally exposed that reality. When Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal, Prime Minister Anthony Eden viewed it as a challenge to British authority and secretly plotted with France and Israel to retake control. The invasion, carried out without U.S. approval, provoked outrage in Washington. President Eisenhower threatened to collapse the pound by selling American sterling reserves, forcing an immediate withdrawal. Eden resigned soon after, his reputation ruined.

Suez was more than a diplomatic disaster, it was a psychological reckoning. The Times later described Eden as “the last Prime Minister to believe that Britain was a great power” (The Times, 1956). The crisis made it clear that no major action could be taken without American consent. As Barnett later remarked, it was “the last thrash of empire” (Barnett, 1986). From then on, Britain’s foreign policy would be framed within the orbit of U.S. strategy.

Cold War, The Bomb, and a New World Order:

After Suez, Britain sought to reclaim status through science, defence, and diplomacy. In the early Cold War, it presented itself as a bridge between the U.S. and Europe, a stabilising influence within NATO and the United Nations. Yet in the new nuclear age, prestige increasingly meant possessing the bomb.

Having contributed significantly to wartime atomic research, Britain was frustrated when the U.S. refused to share nuclear secrets after 1945. Determined not to be left behind, the Attlee government secretly authorised an independent nuclear programme. The first British test in 1952 made the country the world’s third atomic power. Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin captured the mood of determination when he declared, “We’ve got to have this thing over here, whatever the cost, we’ve got to have the bloody Union Jack flying on top of it” (Bevin, quoted in Hansard, 1946).

The bomb offered symbolic parity with the superpowers, but at enormous financial and moral cost. Britain’s scientists and politicians debated whether nuclear weapons provided security or merely the illusion of it. Possessing the bomb allowed Britain a continued seat at the top tables of global diplomacy, but its autonomy was limited. The nation remained influential, yet no longer decisive.

The End of Empire:

The post-war years also brought the rapid retreat from empire. Financial exhaustion, nationalist movements, and changing global attitudes made decolonisation inevitable. Britain’s withdrawal from India in 1947, under the hastily drawn Radcliffe Line, divided the subcontinent into India and Pakistan and triggered the largest mass migration in history.

In the Middle East, Britain’s hold over Palestine collapsed amid conflict between Jewish and Arab communities. Unable to manage the crisis, Britain handed the issue to the United Nations, which voted in 1947 to partition the territory. The following year, Britain withdrew as Israel declared independence and the Arab–Israeli war began.

Elsewhere, independence movements spread across Africa and Asia. By the end of the 1960s, the empire had effectively vanished. What remained was a redefined nation, smaller, pragmatic, and increasingly introspective, but still seeking a role through partnership with America, Europe, and the Commonwealth.

Conclusion:

From 1945 to 1969, Britain underwent a transformation more profound than at any time in its modern history. Victory in war had delivered not renewed dominance but a new identity: from imperial power to democratic partner, from ruler to reconciler. The country that once commanded a third of the globe now measured its greatness not in territory, but in values, diplomacy, and resilience.

As Alfred Lord Tennyson wrote in Ulysses, “We are not now that strength which in old days moved earth and heaven; but that which we are, we are” (Tennyson, 1842). Britain’s post-war story is one of endurance and adaptation, a proud island nation learning that greatness could survive even when empire did not.

Summary of Britain in the 1970’s

The 1970s in Britain are often framed as a decade of crisis, marked by inflation, strikes, political instability and a general sense that the post-war consensus was breaking down. Yet, as with many broad historical narratives, lived experience could be very different. Born in 1967, I grew up through this decade but was largely insulated from its difficulties. My dad worked in a secure engineering role at Ford’s Dunton research and development centre, and family life felt stable and happy. While the national picture suggested turbulence, my personal memories are of first albums, experimenting with my appearance, and a warm household that sheltered me from the anxieties dominating public life. This contrast captures something fundamental about the 1970s: the gap between public hardship and private normality.

Nationally, the decade began with Edward Heath’s Conservative government, elected unexpectedly in 1970. His administration faced accelerating inflation, global economic pressures and an increasingly assertive trade union movement. The early 1970s saw the miners’ strikes, the three-day week and widespread power cuts, events that created a sense that Britain was becoming difficult to govern. Heath also took Britain into the European Economic Community in 1973 for the first time, a move he regarded as essential but which was deeply divisive within his own party (Sandbrook, 2010).

Labour returned to power in 1974 under Harold Wilson, but with only a tiny majority. Despite internal divisions and economic difficulties, his government introduced significant social reforms, including improvements to pensions, housing subsidies and worker protections. ACAS was established to handle workplace disputes more constructively, a recognition of the increasingly fractious industrial climate (Morgan, 2001). Wilson’s surprise resignation in 1976 brought James Callaghan to office at a time when inflation, unemployment and falling productivity were eroding economic stability.

A turning point came with the 1976 IMF crisis. Facing a collapsing pound and a severe budget deficit, Britain was forced to accept a major loan from the International Monetary Fund. The loan required substantial cuts in public spending and wage restraint, angering the unions and damaging Labour’s relationship with its traditional base. Although the economy began to stabilise by 1977, tensions remained unresolved, eventually triggering the Winter of Discontent in 1978–79, when public-sector strikes left rubbish piling up and essential services disrupted (Turner, 2008). 79’ was the year I bought my first album having used taped recordings from the radio previously.

Socially, the decade was one of profound change. The Equal Pay Act (1970), Sex Discrimination Act (1975) and Race Relations Act (1976) reflected growing demands for equality and justice. Feminist voices, including Germaine Greer, highlighted the limits of the freedoms won in the 1960s, while the Women’s Liberation Movement pushed for deeper structural change (Marwick, 2003). Race relations were tense, illustrated by Enoch Powell’s inflammatory rhetoric and the 1976 Notting Hill clashes, but new legislation and the creation of the Commission for Racial Equality signalled attempts to confront discrimination more seriously.

Culturally, the 1970s were remarkably vibrant. Glam rock and artists such as Bowie and Bolan defined the early part of the decade with flamboyance and experimentation. Later, punk exploded as a reaction to economic stagnation and political disenchantment, offering a raw, DIY alternative to mainstream culture. Two-Tone blended punk and ska to address racism directly and bring Black and white youth culture together (Spicer, 2008).

By 1979, Labour had become strongly associated with national dysfunction, despite the complexity of the underlying causes. Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives swept into power following the general election that year, promising clarity, discipline and a decisive break with the past.

Decline or Transformation?

Whether the 1970s should be remembered as a decade of decline or transformation depends largely on where one looks. Economically and politically, Britain undoubtedly experienced severe pressures: inflation, industrial conflict, weak productivity and repeated changes in leadership. From this perspective, the decade appears as the final unravelling of the post-war consensus, culminating in the Winter of Discontent and a widespread belief that the country was ungovernable.

Yet at the same time, the 1970s were culturally and socially transformative. Important equality legislation was introduced, feminist and anti-racist movements grew, and youth culture became more expressive, experimental and politically engaged. Punk and Two-Tone re-energised British music and challenged social boundaries, while everyday life was being reshaped by new technologies, consumer credit, and changing expectations around identity and freedom.

Personal experience adds further nuance. For many families, including mine, the decade felt stable, warm and even exciting, despite the wider pressures. This tension between national anxiety and private normality suggests that the 1970s were not simply a period of decay but a complex transitional moment, messy, conflicted, but ultimately creative and forward-moving.

1980’s

For many of us, the 1980s weren’t just a decade - they were an awakening.

Let’s take a long hard, steady look at Britain in the 1980s, not the nostalgic, rose-tinted version people often wheel out when talking about the decade, but the messy, contradictory reality of a country being pulled apart and stitched back together at the same time. It was the era when Thatcher’s government seemed to dominate every breath of public life, whether you admired her or couldn’t stand the sight of her. Everything, from the economy to culture to the way people thought about work and aspiration, felt like it was being reset. The key is that this reset was not accidental; it was intentional. Thatcher saw herself as breaking with the post-war consensus, the political, social and economic settlement established from 1945 onward which treated full employment, a mixed economy and active social welfare as the foundations of British life (Kavanagh, 1987, pp. 7–9).

At the heart, it could be argued that the 1980s were the decade when Britain finally broke with its post-war identity. Old industries that had defined entire communities, steel, coal, shipbuilding, were fading fast. These sectors had previously been protected by state ownership, union influence and industrial planning, because the consensus approach assumed that the government had a duty to maintain stability and jobs (Kavanagh, 2009). Thatcher rejected that duty as unhealthy. When she came into office in 1979, she prioritised defeating inflation rather than defending employment, adopting monetarist policies that forced interest rates upward and squeezed money supply. The result was economic shock. Unemployment doubled within a few years, rising from around 1.5 million to over 3 million by 1981 (Turner, 2010, p. 71). For some people, this meant opportunity: new money, new business culture, and a sense that the country was shaking off decline. For others, it meant unemployment, boarded-up high streets, and a feeling that the government had simply abandoned them. The divide wasn’t just economic; it was emotional. The sense of ‘two Britain’s’ really took hold.

Politically, the decade was dominated by Thatcherism, not just as a set of policies but as a way of thinking. We can show how privatisation, free-market principles, and a push for individual responsibility reshaped society. Thatcher’s political project was a rejection of consensus-era values. She considered trade union leaders to be unelected power-brokers who distorted markets and prevented national competitiveness. Her belief was that prosperity could arise only from a liberated private sector, not from government-backed collective bargaining (Kavanagh, 1987, pp. 24–28). Thatcherism was therefore not a mild adjustment of economic policy, but a moral repositioning. She spoke in terms of discipline, incentive, reward and punishment, a vision of citizenship where individuals were expected to take their own risks, win their own rewards, and bear their own losses. Whether this was liberation or destruction depended on where you were standing.

The Falklands War plays a big part in Turner’s narrative, not just as a conflict, but as a symbolic moment where Thatcher’s leadership crystallised and a fractured nation briefly united. Before 1982, her government was deeply unpopular, and even her own party questioned her survival. Victory in the South Atlantic transformed her from a divisive economic reformer into a defender of the nation. It reinforced her self-image as a leader of conviction, and it allowed her to argue that the same resolve she showed abroad was necessary against ‘enemies within’ at home, from unions to ‘the culture of dependency’ as she called it (Turner, 2010, pp. 91–96). The Falklands did not repair unemployment, nor did it soothe the social wounds of monetarism, but it reset the emotional mood of the country. The second Thatcher landslide in 1983 was not only a verdict on Labour disarray, it was a vote for authority.

Culturally, there was a lively picture. The 1980s weren’t just politics; they were the decade of bold music, sharper edges, and statements made through clothes, attitudes, and MTV-style imagery. Pop culture, alternative comedy, gritty TV dramas, and the explosion of youth subcultures all reflected the tension of the times. Synthesizers became cheap and accessible. Creativity migrated from pubs and working-men’s clubs to bedrooms, record shops and underground clubs. Unlike the 1970s, which had worn its pessimism openly, the 1980s wore defiance. Turner notes that British pop exploded internationally during this period: bands such as Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet, Depeche Mode, The Human League and Culture Club sold in volumes previously unheard of for UK artists (Turner, 2010, pp. 148–154). From Top of the Pops to the Blitz Club, British youth defined itself not through labour or class, but through spectacle, glamour, irony and sound. This wasn’t escapism; it was a new language for identity.

Socially, Turner shows us a country wrestling with change: class lines being redrawn, new communities emerging, and old loyalties, to unions, institutions, traditions, weakening. In the consensus period, unions had been central to political life; governments negotiated wage deals and industrial planning with them directly. Thatcher reversed that model entirely. New laws required ballots before strikes, ended the closed shop, and made unions liable for unlawful industrial action (Kavanagh, 1987, pp. 31–35). These were not technical reforms; they deliberately transferred power away from organised labour and toward employers. Riots in Brixton, Toxteth and Handsworth exposed the racial and economic fractures that had festered beneath the surface for decades (Turner, 2010, pp. 120–123). What had been sold as “freedom” did not feel liberating to communities who lost not only jobs, but identity, status and future. There’s a constant back-and-forth between modernisation and loss, as if every step forward required something cherished to be left behind.

Above all, we can see the impression of a decade that was electric, divisive, and impossible to ignore. Even if you didn’t like the direction of travel, you couldn’t deny that something huge was happening. Britain was becoming the country we now recognise today, for better or for worse.

Politics — Thatcher was both architect and wrecking ball.

The political landscape of the 1980s was dominated so completely by Margaret Thatcher that it’s almost impossible to talk about the decade without talking about her. Turner’s take isn’t worshipful or hostile, more an attempt to show how her presence shaped everything, even for people who despised her.

She wasn’t simply a Conservative Prime Minister; she was a force of nature. Policies weren’t just technical decisions; they were expressions of a worldview. She pushed the idea that Britain should stop apologising for itself, start competing again, and adopt a hard-nosed, almost American style of ambition. For some, it was invigorating. For others, it felt like a bulldozer ploughing through communities that couldn’t keep up. Thatcher’s belief that compromise had crippled previous governments was central: Heath and Callaghan had both tried to placate unions, and both had failed. Thatcher vowed to never be pushed off the path. Her famous declaration, “The lady’s not for turning”, was not a slogan, but a method of government.

The political battles, with the miners, the unions, sections of her own party, all reflected this bigger conflict about what Britain should be. The decade feels like one long, fierce argument about the soul of the country. Thatcher did not treat politics as consensus-building; she treated it as conviction. Kavanagh notes that Thatcher was respected rather than loved, her vote share never exceeded the low 40s, but the fragmentation of the opposition meant she dominated the Commons (Kavanagh, 2009). Britain didn’t crown her; it couldn’t remove her.

Economics - Winners, losers, and the great sorting-out.

The economy wasn’t just numbers on a Treasury graph; it was everyday life. Industries that had been the backbone of Britain for generations were collapsing. Mines, factories, shipyards, towns built on these trades watched them fall away. Monetarism did reduce inflation, but at the cost of mass unemployment, business closures, and a generational loss of industrial skills (Turner, 2010, pp. 87–90). It also produced a new aristocracy: finance, speculation, commercial services. London boomed while Liverpool sank. Regional inequality hardened into identity.

Privatisation wasn’t just a policy shift; it was cultural. Thatcher believed that “popular capitalism”, the idea of millions holding shares, would replace the old collective instincts. British Telecom, British Gas, Rolls-Royce, British Airways, and regional water authorities were all sold off. The policy did initially expand ownership, but those shares quickly concentrated into the hands of large investors and institutions, revealing the ideological nature of the project. As Kavanagh observes, privatisation altered not only business but the entire social understanding of citizenship: from rights and welfare to contract and risk (Kavanagh, 1987, pp. 43–47).

The Big Bang of 1986 completed the transformation. Turner notes it as one of the decisive moments of the decade: the abolition of fixed commissions, the end of rigid trading structures, and the influx of foreign capital into the City (Turner, 2010, pp. 176–179). It was the birth of the modern financial centre. It also accelerated new inequalities. Those who adapted made fortunes; those who couldn’t were declared obsolete.

For some people, the collapse of the old structures brought opportunity. I know, because I was one of them. My first small fortune came not from steady work or a career, but in the aftermath of the Great Storm of 1987. Trees were down everywhere, roof tiles scattered, power lines torn apart, roads blocked. Nobody was prepared, not councils, not companies, not utilities. People needed help immediately, and I threw myself into clearing, hauling, cutting, moving, and building, whatever was required. I learnt on the job. The old Britain would have waited for authorities or unions; Thatcher’s Britain rewarded whoever acted first.

Society - A country changing its shape.

Socially, this is where we really capture the lived experience. The traditional class system didn’t vanish, but it loosened. People began reinventing themselves. The idea that “where you come from decides who you are” started to crack. Brand-new categories, entrepreneurs, self-employed, consultant, replaced miner, fitter, steward. That transformation was not purely voluntary. Many felt forced into it when the old world collapsed. Welfare provisions became increasingly means-tested; responsibility and risk were internalised. For the first time since the foundation of the welfare state, the government explicitly announced it was ‘no longer a universal provider’ (Kavanagh, 2009).

Race, gender roles, sexuality, all these were shifting too. Britain was becoming more diverse, more outspoken, and more aware of itself. Some embraced the change. Others resisted it fiercely.

Culture - Attitude, noise, and the pop explosion.

The cultural shifts of the 1980s weren’t happening quietly. This was the era of bold outfits, big hair, synths, neon colours, and a pop scene that swung between glam excess and gritty realism. Turner argues that British culture, more than any other European culture, reinvented itself in the 1980s, producing a wave of music and art that conquered the United States (Turner, 2010, pp. 149–153). Television transformed too: alternative comedy attacked the moral assumptions of earlier decades, dramas portrayed working-class life without sentimentality, and satire sharpened its teeth. There was swagger, Britain seemed to find its voice again.

Media & Technology - Faster, flashier, more influential.

Technology didn’t dominate life like it does today, but the seeds were planted. The home computer appeared, giving children and teenagers a new way to learn and play. The ZX Spectrum encouraged a DIY ethos that mirrored the New Romantic music scene. Synthesizers democratized creativity just as financial deregulation democratized risk. The media became hungrier, more aggressive. Tabloids learned how to shape public mood. Thatcher understood the new ecosystem instinctively; she used broadcast media to project authority and treated the press as a battlefield rather than an audience (Turner, 2010, pp. 58–63).

Daily Life - The feeling of living through upheaval.

Turner doesn’t just describe big events; he captures the texture of everyday life. Shopping habits changed. Supermarkets replaced butchers and bakers. Microwaves, VCRs and home entertainment systems became aspirational markers. Credit expanded. Debt became a personal instrument rather than a failure. Thatcher framed this shift as self-reliance; critics saw it as survival. The experience of the 1980s varied wildly depending on where you lived and what work you did. For some, it was the decade opportunity finally arrived. For others, it was the beginning of a long decline.

The tension between optimism and despair is constant. It defines the era.

National Identity — Britain trying to redefine itself.

If the post-war decades were about managing decline, the 1980s were about refusing to accept decline at all, even if the refusal came with a cost. The Falklands War matters here, not just as a conflict but as a symbolic moment when Britain told itself it still had strength, still had purpose. Whether that was genuine or just good PR is up for debate, but the emotional impact was real. Turner argues that the war gave Britain a new, if temporary, sense of self-confidence, an energy that Thatcher harnessed to justify her domestic battles (Turner, 2010, pp. 92–95).

By the end of the decade, Britain felt like a different country. More confident, more divided, more consumer-driven, more global, and far less rooted in the world that existed before.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The 1980s marked one of the most transformative decades in modern British history. Margaret Thatcher’s 1979 election victory ushered in not just a change of leadership but a decisive shift in political philosophy. Her belief that individuals, not the state, should take primary responsibility for their lives signified a break from the post-war consensus (Morgan, 2013). Thatcher’s famous assertion that “there is no such thing as society” came to symbolise the ideological thrust of the era, which emphasised free markets, self-reliance and reduced state intervention (McSmith, 2011).

This shift produced what many historians describe as a new ‘them and us’ society, one that sharply divided the ‘haves’ from the ‘have-nots’. The ‘haves’, including Sloane Rangers, Yuppies and beneficiaries of financial deregulation, felt empowered by new opportunities for homeownership, investment and upward mobility. Thatcher’s supporters viewed her as reviving Britain’s confidence and modernising its economy after years of stagnation (Young, 1989; Jenkins, 2006). Right to buy, in particular, was celebrated for expanding homeownership, even if its long-term consequences were less positive.

Critics, however, argue that Thatcherism deepened inequality across class, region and income. Stewart (2013) and Marwick (2003) highlight how industrial decline hit working-class and northern communities hardest, while the decision not to replace sold council housing eroded the social housing sector (Morgan, 2013). House prices soared, mortgage debt increased and homelessness rose sharply (Childs, 2005). These developments intensified social stress and contributed to a sense of dislocation in many communities.

Cultural resistance to these changes was strong. Music, comedy and new media channels provided outlets for frustration, anger and social critique. Urban tensions erupted into riots in Brixton, Toxteth, Handsworth and Chapeltown in 1981, fuelled by long-standing anger about policing, inequality and the SUS laws (Marwick, 2003) "Sus law" is an informal term for a former British law based on the 1824 Vagrancy Act that allowed police to stop, search, and arrest people suspected of loitering with the intent to commit a crime)). Songs like The Specials’ Ghost Town became touchstones of the era’s social mood, capturing what Turner (2010) calls the cultural soundtrack of Thatcher’s Britain. At the same time, alternative comedy emerged as a reaction to racism, sexism and social conservatism, with the Comic

Strip, Spitting Image and Channel 4 offering platforms for dissent (Stewart, 2013).

The 1984-85 Miners’ Strike became the defining industrial conflict of the decade. The government’s plan to close unproductive pits threatened thousands of jobs. Arthur Scargill and the National Union of Mineworkers resisted, but without a national ballot the strike was deemed illegal. Thatcher’s description of the unions as the ‘enemy within’ exemplified her determination to break union power (Clarke, 2004). The confrontation at Orgreave, where thousands of police clashed violently with pickets, left lasting trauma in mining communities. As Turner (2010) argues, the strike’s defeat reshaped Britain’s industrial landscape for generations.

Meanwhile, the government’s handling of the HIV/AIDS crisis and the passage of Section 28 (Section 28 was a UK law passed in 1988 that prohibited local authorities from "promoting homosexuality". It was repealed in Scotland in 2000 and in England and Wales in 2003) deepened hostility among LGBTQ+ communities and their allies. Hadley (2014) notes that the timing and tone of these policies reinforced stigma at a moment when compassion was needed most. Thatcher also faced backlash from the Establishment itself. Oxford University’s refusal to award her an honorary degree in 1985 represented a remarkable rebuke, while the Church of England’s report Faith in the City criticised the government for worsening urban poverty (Jenkins, 2006; Stewart, 2013).

Another defining episode was the Hillsborough disaster of 1989. Although the Taylor Report strongly criticised police failures, Scraton (2017) shows how the government reacted cautiously, reluctant to endorse findings that might undermine public confidence in policing. The media narrative, especially The Sun’s false allegations, further fuelled a sense of betrayal in Liverpool.

By the decade’s end, a new youth culture emerged in the form of acid house and rave culture. Turner (2010) argues that these movements briefly transcended class and regional differences, fostering a sense of unity that contrasted sharply with the decade’s divisions.

Thatcher finally fell in 1990, undone by Cabinet divisions, economic difficulties and growing hostility over Europe. Clarke (2004) highlights Geoffrey Howe’s resignation speech as the moment that decisively shattered her authority. Yet Thatcherism’s legacy endured: as Stewart (2013) and Turner (2010) argue, Britain today still lives in its long shadow, shaped by the social, economic and cultural transformations of the 1980s.